Blågrön infrastruktur (BGI) är ett angreppssätt på planering och urban design som förlitar sig på förmågan hos naturliga element, såsom växter och vatten, att skapa resilienta och trivsamma städer. När Herbert Dreiseitl, som är en av de världsledande personerna inom detta fält, beskriver vikten av BGI är det mot bakgrund av bland annat hans arbete i Portland, Oregon och Bishan-Ang Mo Kio Park i Singapore. Projekt som enligt vissa banar väg för utvecklandet av en helt ny syn på stadens infrastruktur och stadens form.

Herbert Dreiseitl is an urban designer and landscape architect. As director of Rambøll’s Liveable Cities Lab and founder of Atelier Dreiseitl, he uses water and art for inspiring solutions to urban challenges all over the world.

What could be a model for future cities? Nature may have some of the answers. Comparing structures in the natural environment with those from urban settings, a significant difference can be seen. Nature works on principles of flexibility and resilience, a dynamic reaction and balance to any event, from a soft change to the unexpected disaster. Given the enormous impact of, say, a flood on erosion, hurricanes that destroy forests, avalanches or volcanoes that wash away mountains and hillsides, it is incredible how quickly ecosystems adapt to new conditions. Over time one hardly recognizes the impact of the disaster; only experts with domain knowledge can tell the difference. This flexible and dynamic response of ecosystems is unique; some lessons may be learnt from this in the design of urban settings. Blue-Green Infrastructure (BGI) is an approach to urban design that relies on natural elements (flora and water) which are deployed in strategic ways. BGI is not yet properly understood in its true function and value to a city and its inhabitants. But it is the backbone for liveability, a repository of resources that balances and stabilizes life processes. We cannot easily measure, count and quantify the value of BGI to urban structures, not in the way that we might, say, hard forms of engineered infrastructure. BGI can never be a prefabricated décor that is countable, statically-determined and never-changing. Vegetation is in a permanent state of evolution, responding to daily rhythms, seasonal changes and the many stages of aging and renewal. All phases coexist in a living system. In a natural forest this process of renewal takes place all the time; life and death coexist. It is a resilient living system.

In what ways does BGI offer resilience and liveability?

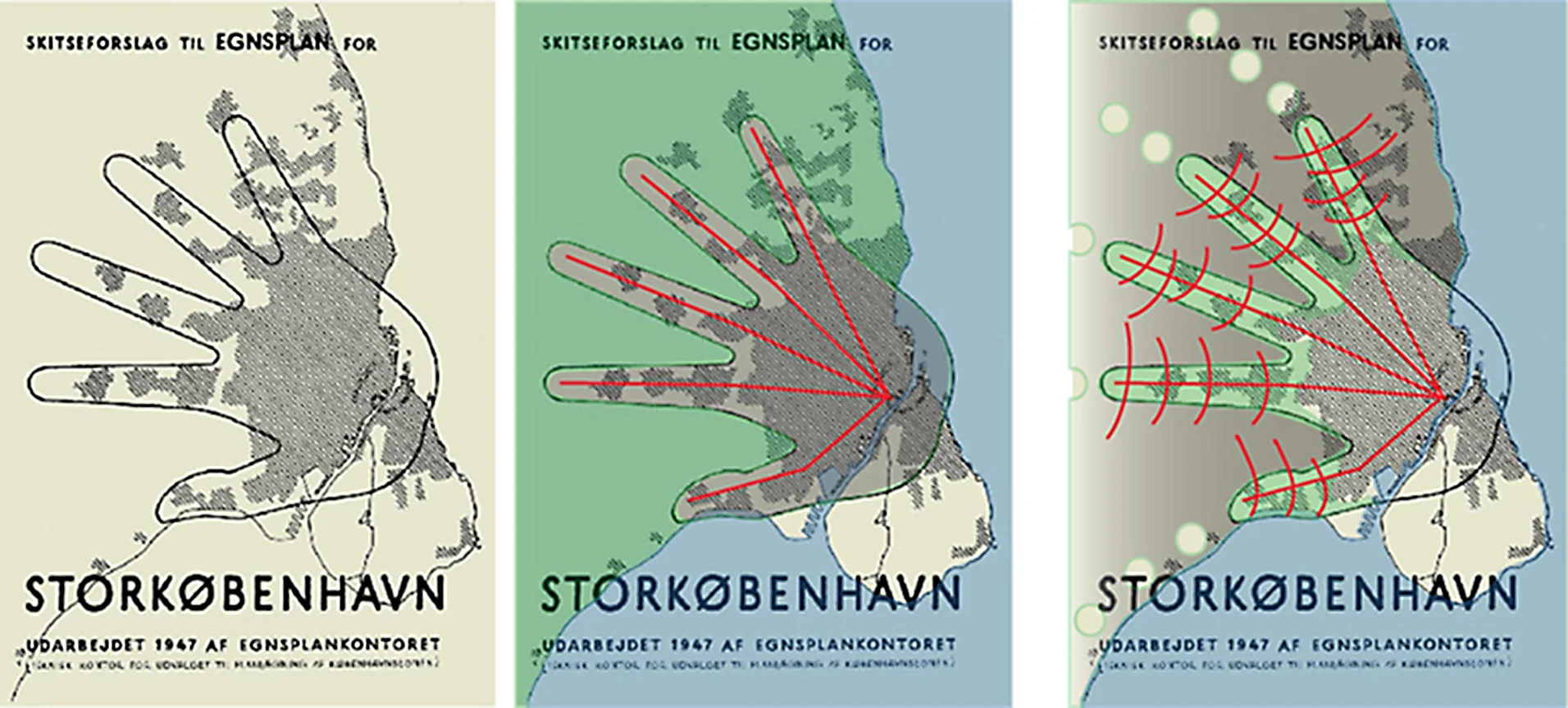

UN statistics show that 60% of the world’s city will face water shortage by 20251. Ironically many cities across the globe will also experience, in parallel, the devastation of floods. Flood and drought happen more frequently, adversely affecting food production, water security, energy, mobility and public health. There is a trend of “too much at one time, too little at other times”. Fast growing urban sprawl continues to cover the surface of the planet with asphalt and concrete. Instead of slowing down rainwater runoff, holding it back and avoiding concentrations, this type of development results in large quantities collecting at the same time and same place. These are the conditions for urban flooding. There are other consequences to this question of water conveyance: urban streams often lack water in dry periods. As a result, temperatures rise and oxygen is low. Natural habitats die; fish and plant life suffers. BGI can mitigate these conditions, creating natural corridors that are highways for biodiversity. On microclimate, BGI has a significant effect. In the absence of blue and green there is no filtration of air, no holding back of micro particles (wind-blown dispersal). As a result, there are higher dust concentrations which contribute to conditions that are unhealthy. Research in the city of Hamburg showed clearly that in city centers that have less green and water-bound surfaces, concentration of dust particles is significant higher. Streets with trees have less dust than streets without trees and planted greens. According to WHO estimates, 7.1 million people died in 2012 as a direct result of air pollution. In most parts of the world, built urban fabric is not only growing, it is also appropriating natural landscapes. This might not be a problem itself were it not for the way we design or engineer these urban settings. The fragmentation that occurs simply cuts the breath out of the living environment. The growth of a city, its impact on surrounding countryside, is therefore an important consideration. It is common that many cities lose almost all their ecological structures and green corridors including open waterways, productive landscapes and park networks. Most successful modern cities, on the other hand, manage to keep and develop their BGI. Among these cities is Copenhagen with its Green Finger Plan from 1947. It is a strategy that was easy to understand: leave corridors free from construction. Today Copenhagen is among the greenest cities with the highest livability and lifestyle rankings in the world. (Green Capital of Europe 2014, Nr1 in Mercury Report 2014) Whatever scale and dimension of the development, BGI is an underlying fundamental that connects people with their environment. Without water systems and green structures (and their proper management) there is no foundation for long term sustainability. It is the DNA for any healthy urban development, the medicine to keep cities alive and vibrant.

It is common that many cities lose almost all their ecological structures and green corridors including open waterways, productive landscapes and park networks. Most successful modern cities, on the other hand, manage to keep and develop their Blue-Green Infrastructure. Among these cities is Copenhagen with its Green Finger Plan from 1947.

Lastly, the character of a place is its gestalt. It might be one of the most important factors for any human settlement, a key ingredient in liveability. Blue and green elements offer a platform for human interaction and place-making. There are many questions to be answered about the integration of BGI into cities. What functions and qualities must these spaces fulfill today and in the future? How can we create living systems that save natural resources, filter, clean and regulate water supply, balance temperature, produce good air, and increase natural habitats? What are the basic principles, processes and methods to integrate BGI in cities of today and in the future?

These questions must extend to the search for strategic policy making tools and good governance structures. Detailed knowledge about Blue-Green living systems, about materials and integrated technologies, have to be developed and experts must be called in during the early stages of the project, and importantly, be taken seriously. Urban landscape architecture should have a higher priority in a development and not be seen as byproduct. And since these projects affect people, there must be public engagement and society building. Liveability is contingent on ‘likeability’, the making of stronger emotional and spiritual connections. To give hope to denser growing cities we have to create partnerships that balance the needs of people and the environment within urban landscapes in a more respectful way.

Photos: Atelier Dreiseitl, Tom Good, Heidenreich

It seems we have all technology and knowledge available today; yet there is a lack of implementation. There is a discrepancy between what designers and engineers can create with what governments can activate in reality. This dilemma we cannot effort in the future

Herbert Dreiseitl