When citizens step in: planning from below in the absence of statutory planning. Experiences from Galicia, Spain.

När forskaren Marlies Meijer presenterar sina studier av lokala planeringsinitiativ i Spanien så förefaller handlingskraften och det lokala engagemanget nästan som en naturlig konsekvens i ett land där grundläggande planeringsinstrument saknas. Särskilt intressant blir det när Meijer även kan se liknande tendenser här i Sverige

Marlies Meijer is a PhD Candidate in Spatial Planning and Human Geography. Radboud University, the Netherlands.

Imagine a country with incomplete statutory planning. A country where not every municipality has a land allocation plan (detajlplan) and where strategic plans (strukturplan) are rare. Would this make planning less complicated? Would it be easier to develop new initiatives, if there are less formal procedures to be followed? And would there be more possibilities for bottom-up initiatives? These questions were asked when I held a presentation about planning practices in Galicia, before an audience of Swedish planning professionals. I asked myself the same questions, before I left to do research in this autonomous region of Spain. Looking back, I know now that these questions are not easily answered: in the absence of statutory planning, spatial coordination can be extremely complicated. With this paper I will allow you a glance behind the scenes of (bottom-up) planning practices in Galicia.

Most communities started developing initiatives, because the local government was unable to meet their basic needs. For some projects they received subsidies from the regional government or EU rural development funds. However, most projects were financed with their own resources and expertise. Here is a football field, initiated by the local football club in Muimenta.

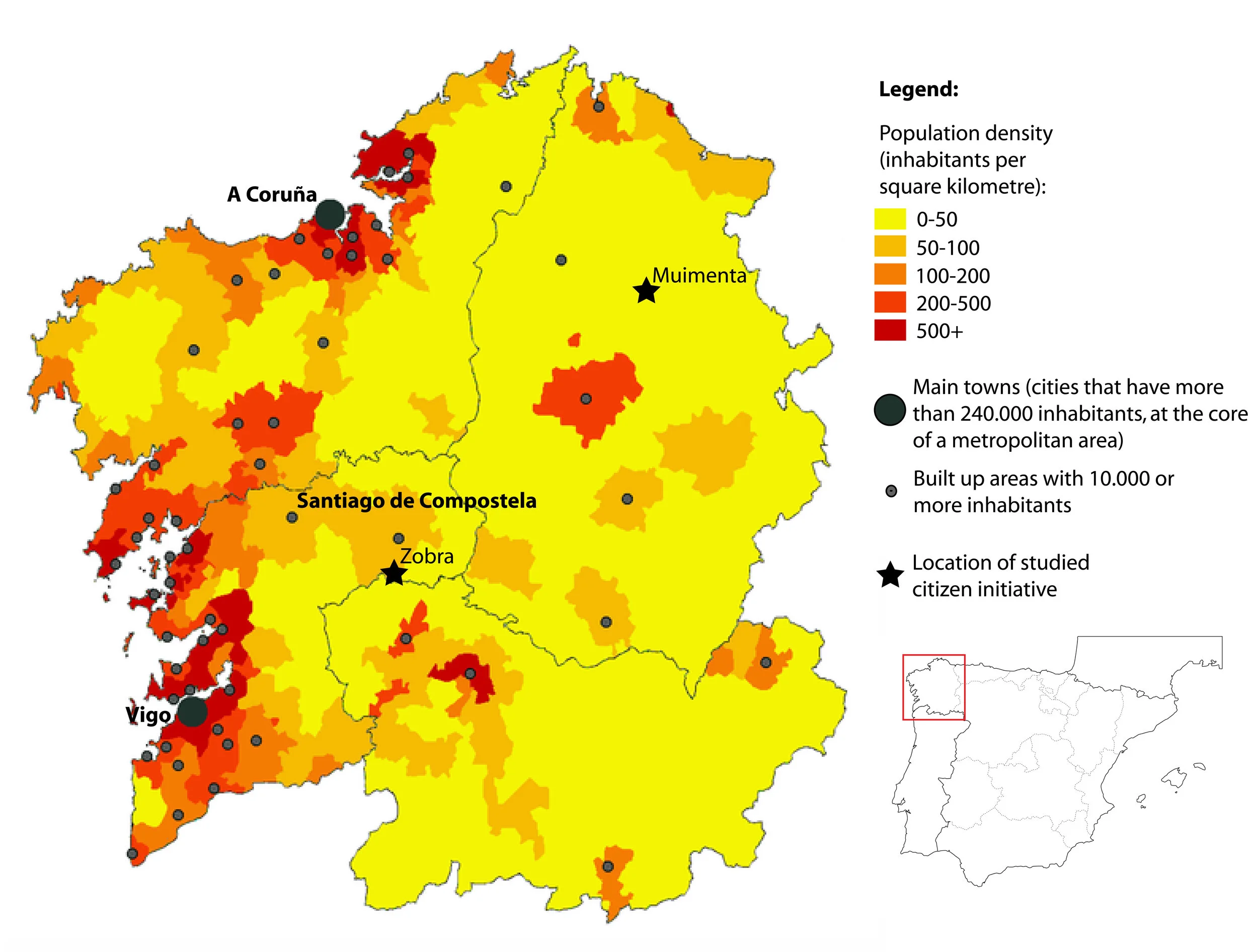

Galicia is a country where statutory planning is not self-evident. About one third of the municipalities have not adopted the PXOM (Plan Xeral de Ordinación Municipal) yet, the 2009-law that obligates municipalities to draw up land allocations plans. Another third has land allocation plans that are out-dated. This implies that in Galicia economic and social developments are not incorporated in territorial strategies. Furthermore, building permits are, in the absence of statutory planning, often granted on the basis of individual judgments of civil servants or the (political responsible) mare. On the one hand the absence of statutory planning simplifies spatial planning and leaves space for flexibility; though national and regional regulations are still applicable. On the other hand, the informal negotiations involved with individual judgments complicates the development of new initiatives and leave a grey area for clientalism and illegal planning practices.

Apart from the Atlantic metropolitan coastal area, with A Coruña, Santiago de Compostela and Vigo as principal cities, Galicia is a very rural country. The more mountainous eastern part of Galicia is subjected to severe depopulation and economic decline, resulting in abandoned villages and an ageing population. Municipalities in Galicia are often small in population numbers and have little means to practice adequate spatial planning. Depopulating municipalities are not compensated for the extra costs involved with the loss of population. As a consequence, basic facilities (education, health care, access to public transport) are closed or centralized in larger towns. Especially for peripheral hamlets the travel time to visit a doctor or to go to primary school can run up to 1.5 hours. Citizens are left to deal with this situation themselves. In this vacuum, where spatial planning does not fulfill the needs of remote living citizens, some citizens take faith into their own hands. This led to bottom-up planning practices, developed by communities that believe they can plan and implement their own medical care centers, sports arenas, meeting places and infrastructure. Below I will list a two examples that illustrate how bottom-up planning practices are performed by communities. In the conclusion of this article I will reflect on these examples and their implications.

All projects in Muimenta were developed outside the realm of governmental planning. Their latest project is the renovation of the old school and neighboring church, shown on this picture.

Muimenta, a busy village

Muimenta is an enterprising small village (800 inhabitants) that develops plans since the 1980’s. Their efforts started with the development of a football field, initiated by the local football club and (financially) supported by the wider community. This project inspired the community to built a medical centre in 1986, when their calls for nearer medical facilities were not adopted by the municipality. At that time inhabitants of Muimenta had to travel more than 30 minutes by car to visit a general practitioner. In the absence of public transport, an increasing group of elderly was unable cover this distance by themselves. With their own means the community built a medical centre in the middle of their village, on a piece of collectively owned land. Now the centre is staffed with a nurse and every week a general practitioner holds practice. Since then the inhabitants of Muimenta built a large exposition hall on the same terrain for cattle markets and local festivals, a recreational area near the river and they extended the sports arena with covered strands, a canteen, dressing rooms and a tennis court. Their latest project is the renovation of the old school and neighboring church. With the rehabilitation of cultural heritage a group of retired villagers hopes to pass on their history to a younger generation and to attract some tourists.

All projects were developed outside the realm of governmental planning. At first, the municipality of Cospeito expressed little enthusiasm for Muimenta’s plans, and did not grant building permits for their projects. However the community never felt that they were doing something illegal:

“No, it is a-legal [with irony], that is different from doing something illegal. […]For example, when we built the sports canteen, we had to do it a-legal because of a defect at the municipality, not because we had a problem. The municipality did not catalogue [allocate] these terrains as a sports facility, so we were not allowed to build there. [...] Only according to the law we did something illegal, but morally not as the terrain was in use as a sports field for more than 35 years”

Apart from the Atlantic metropolitan coastal area, Galicia is a very rural country.

Zobra, striving for independence

Zobra is a parish located in the outer fringes of the municipality of Lalín, central in Galicia. Besides several small settlements Zobra covers a collective owned monte of 1400 ha. Besides private and public (government-owned) property, Galicia knows a third type of land ownership: collective owned private property, popularly termed as monte. In the past monte was used by parish communities to pasture cattle, for bee-keeping, mining and wood production. Now most montes lost their function and have become abandoned or in search for new purposes. The monte of Zobra is one of the largest in size, it’s surface even exceeds the territory of some municipalities in Galicia. The size and altitude of Zobra’s monte attracted attention from a large multi-national wind turbine company, that already built turbines on several other montes in Galicia. While the municipality of Lalín already sold concessions to this company, the community of Zobra resisted to these plans. They preferred the development of touristic facilities as a sustainable alternative use for their monte. For Zobra it was important to establish as much independence from governmental budgets as possible: their relationship with the municipality has been problematic since the end of Franco’s regime and most requests for better facilities were refused. That Lalín sold the concessions before consulting Zobra as the legal owner of the monte has been exemplary.

The resistance of the parish did not avert the construction of wind turbines, though a journey to court did result in a fair compensation. The community decided to reinvest this compensation in a touristic accommodation and routes. Moreover, with this compensation and the extra income generated by the touristic facilities, Zobra is now able to employ an office with eight people and save a larger budget for maintenance of roads and fire prevention. Like in Muimenta, the parish board hopes that with the preservation of economic activities and basic facilities, young people are less prone leave the community and willing to take on some responsibilities themselves in the future.

Conclusion

Muimenta and Zobra are not the only Galician communities that decided to take faith into their own hands. During my research stay in Spain I visited and interviewed eight other examples of planning practices from below. Most communities started developing initiatives, because the local government was unable to meet their basic needs. For some projects they received subsidies from the regional government or EU rural development funds. However, most projects were financed with their own resources and expertise. Planning from below is not an easy path to walk in Galicia. Besides financial barriers, more than half of the interviewed examples experienced problems with authorities in the initial phase of the project, like Muimenta and Zobra did. Permits are not easily granted for such innovative practices. As a (disillusioned) citizen remarks: we had to ply the mare with liquor before we got the long promised building permit for our (already build) sports arena.

Nevertheless, both Muimenta and Zobra, as well as other examples, have been planning and implementing projects for several decades. During this period they established more satisfying relations with authorities. In Muimenta the municipality does not object to their projects anymore and pays for electricity and heating. Nowadays they partly finance new projects and activities as well. Most projects have proven their success over time. Depopulation is less severe here as in other surrounding parishes, as the community has been able to maintain employment, public facilities and social housing. For Zobra, the possibility of self-governance took the sting out of most conflicts with local governments. Both communities felt that they did a better job than the municipality could have done, if they had made plans. They argue that their knowledge of the territory and local needs could not have been replaced by the analyses policy-makers make at distance.

In Muimenta depopulation is less severe as in other surrounding parishes, as the

community has been able to maintain employment, public facilities and social housing.

Epilogue

A year after I visited Galicia, I went for a two month research stay to Sweden. Also here I visited examples of citizen initiatives and researched their relation with local governments and higher level authorities. One of my first encounters with Swedish planning professionals was when I presented my Spanish case study results at Centrum för Kommunstrategiska Studier, part of Linköping University. At that time the examples from Spain sounded exotic, but also in Sweden I visited quite some examples of planning practices from below. Like in Galicia, the Swedish countryside is vast and sparsely populated. Though statutory planning is well embedded in Swedish governance, not all municipalities have the means to provide proximate basic facilities for all inhabitants. And also in Sweden most communities I interviewed felt they did a better job than the municipality ever could have done.

Marlies Meijer

For further reading: An elaborate analysis of Galician planning practices from below was published in the Spanish Journal of Rural Development: Meijer, M., Diaz-Varela, E., & Cardín-Pedrosa, M. (2015). Planning practices in Galicia: How communities compensate the lack of statutory planning using bottom up planning initiatives. Spanish Journal of Rural Development, VI(1-2), 65-80. doi:10.5261/2015.GEN1.08